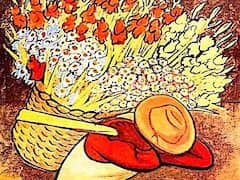

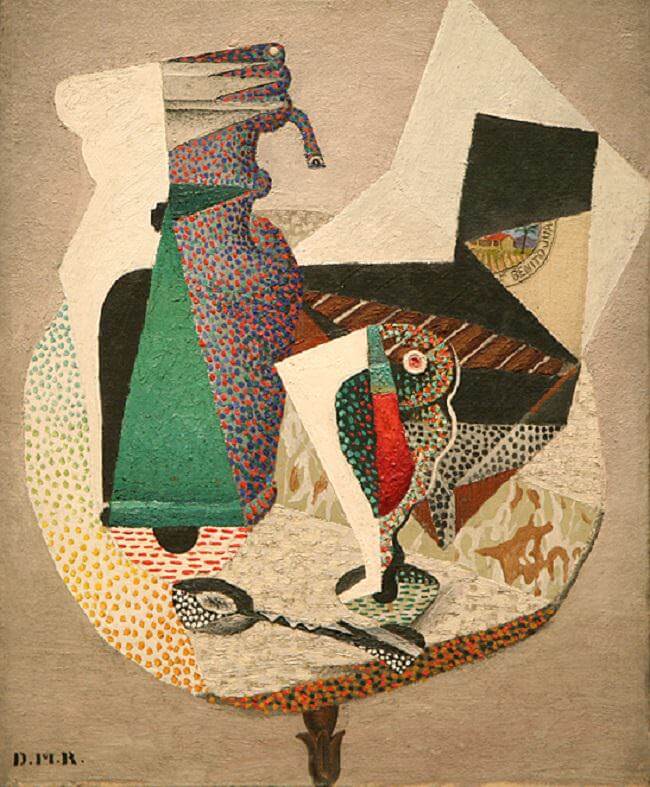

The Cafe Terrace, 1915 by Diego Rivera

When Rivera returned to Paris in late March 1915, he found a city radically changed by the onset of war. As Paris itself was only seventy-five miles from the front lines, the streets were routinely filled with soldiers, and those men not in uniform were met with curfews, suspicion, and in some cases, open hostility. The artistic community in Montparnasse had dispersed. Braque and Apollinaire were among the many artists now in the trenches, while others had decamped to neutral zones to avoid conscription. Salons were suspended, numerous galleries were closed, and buyers were scarce. This was a period of great hardship for many of the artists who remained in the city, including Rivera.

The Café Terrace was produced in Paris in such a climate. The painting almost certainly designates La Rotonde, the café so renowned for its sunny terrace that it was nicknamed "Raspail beach," after the Parisian boulevard on which it was located. Its tables - which resembled this one - were consistently popular with artists, not least because its owner accepted paintings as payment for meals. The Café Terrace features a decanter filled with brilliant green liquid, suggesting absinthe, the potent liqueur that was prepared with water poured over sugar through a slotted spoon. Though banned early in the twentieth century, it was famously consumed and depicted by Paul Cezanne, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, and Vincent van Gogh; here, it signifies the bohemian culture of Paris lost with the onset of war. A particularly prescient and jarring element underscores the wartime context - the pattern suggesting camouflage in the central swathe of the table. Camouflage, invented in the early days of World War I, was developed by artists, including avant-garde artists whom Rivera knew.

This composition, pervaded by the colors green, white, and red, also bears witness to Rivera's primary allegiance to Mexico and reflects his concerns regarding the political climate there. An open cigar box on the right side of the composition contains a landscape in miniature and a label that reads "Benito Jua." The allusion is to Benito Juárez, the nineteenth-century indigenous revolutionary, reform leader, and first president of republican Mexico, who was a powerful symbol in relation to contemporary events.